In recent years, China has repeatedly tightened controls on rare earth exports and related processing technologies. These moves—ranging from export licensing requirements to restrictions on overseas cooperation and end-use limitations—send a clear and consistent message to global markets: critical resources are no longer treated as ordinary commodities; they are strategic instruments.

From a business and supply-chain perspective, China’s use of rare earths as leverage offers several important lessons.

- Real Competitive Advantage Comes from Irreplaceability, Not Price

Rare earths can be used as leverage precisely because they are difficult to replace in the short term. Alternative sources may exist, but not at comparable scale, quality, cost, or processing depth.

For businesses, the implication is straightforward:

- If your product or service is easily replaceable, your bargaining power is limited.

- Companies that control key materials, core technologies, or specialized processes hold structural advantages.

A critical question every firm should ask is:

Are we a “nice-to-have” supplier—or a short-term non-substitutable one?

- Supply Security Is Overtaking Ultra-Low Cost

For years, global sourcing decisions were driven by a single principle: buy from the cheapest supplier. Rare earth restrictions demonstrate the weakness of that approach when policy risk enters the equation.

Today:

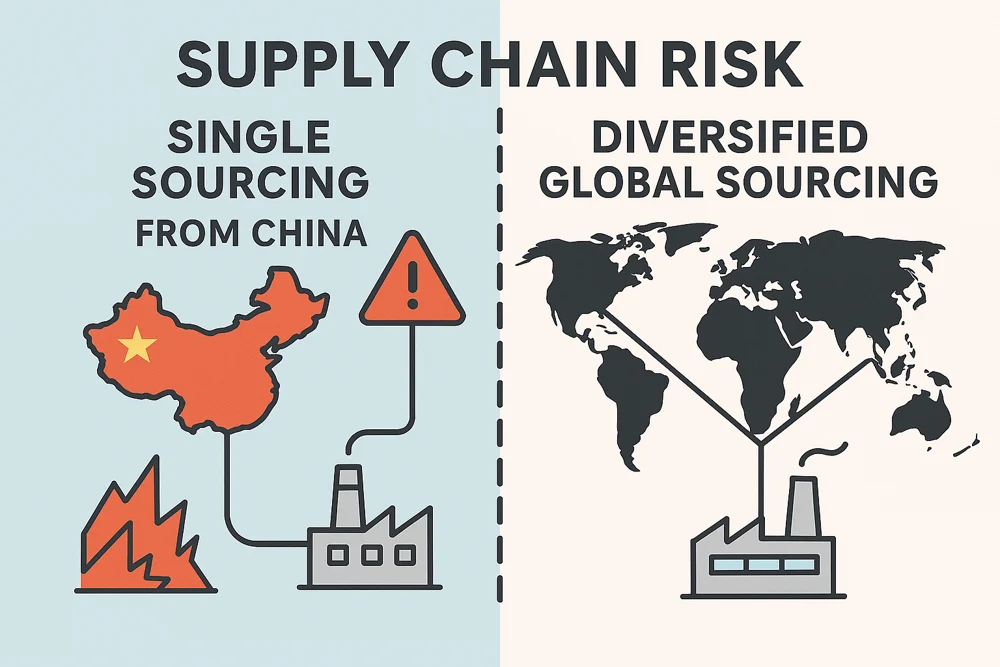

- Single-country and single-supplier sourcing models carry growing risk.

- Diversified sourcing, even at higher unit cost, is becoming a baseline requirement.

Predictability and continuity of supply are being repriced, and businesses that ignore this shift do so at their own peril.

- Compliance Is No Longer About Products Alone—End Use Matters

Modern export controls focus not only on what is shipped, but also:

- Who the end user is

- What the product will be used for

- Whether it touches sensitive sectors such as defense, semiconductors, or advanced manufacturing

For exporters and trading companies, this raises the bar significantly:

- Customer due diligence is becoming unavoidable

- End-user statements and use-case disclosures are increasingly detailed

- “Ship and forget” is no longer a viable operating model

In many cases, the real risk is not the cargo, but liability after delivery.

- Geopolitics Has Become a Hidden Operating Cost

Many companies only realize the impact of geopolitics when shipments are delayed, licenses are denied, or contracts are frozen. By then, the financial damage is already done.

Going forward:

- Policy risk must be factored into pricing and margin calculations

- Contracts need flexibility to address regulatory shifts

- Heavy exposure to politically sensitive supply chains is, in itself, a risk position

Geopolitical stability is no longer an external assumption—it is an internal cost factor.

- For SMEs, Early Positioning Beats Fast Reaction

Large multinationals can absorb shocks through global footprints. Small and mid-sized firms often cannot. For them, preparation matters more than reaction speed.

Practical steps include:

- Identifying early whether products involve strategic or dual-use materials

- Building alternative suppliers and markets before disruptions occur

- Treating compliance and risk management as core operating costs, not optional extras

Conclusion

China’s repeated use of rare earth controls is not an isolated tactic—it is a repeatable and predictable policy tool.

For businesses, the key takeaway is not choosing sides, but ensuring resilience:

The future belongs to companies that cannot be easily “cut off” by any single policy decision.

In an era of strategic trade, success depends not only on efficiency, but on supply-chain resilience, regulatory awareness, and long-term strategic foresight.